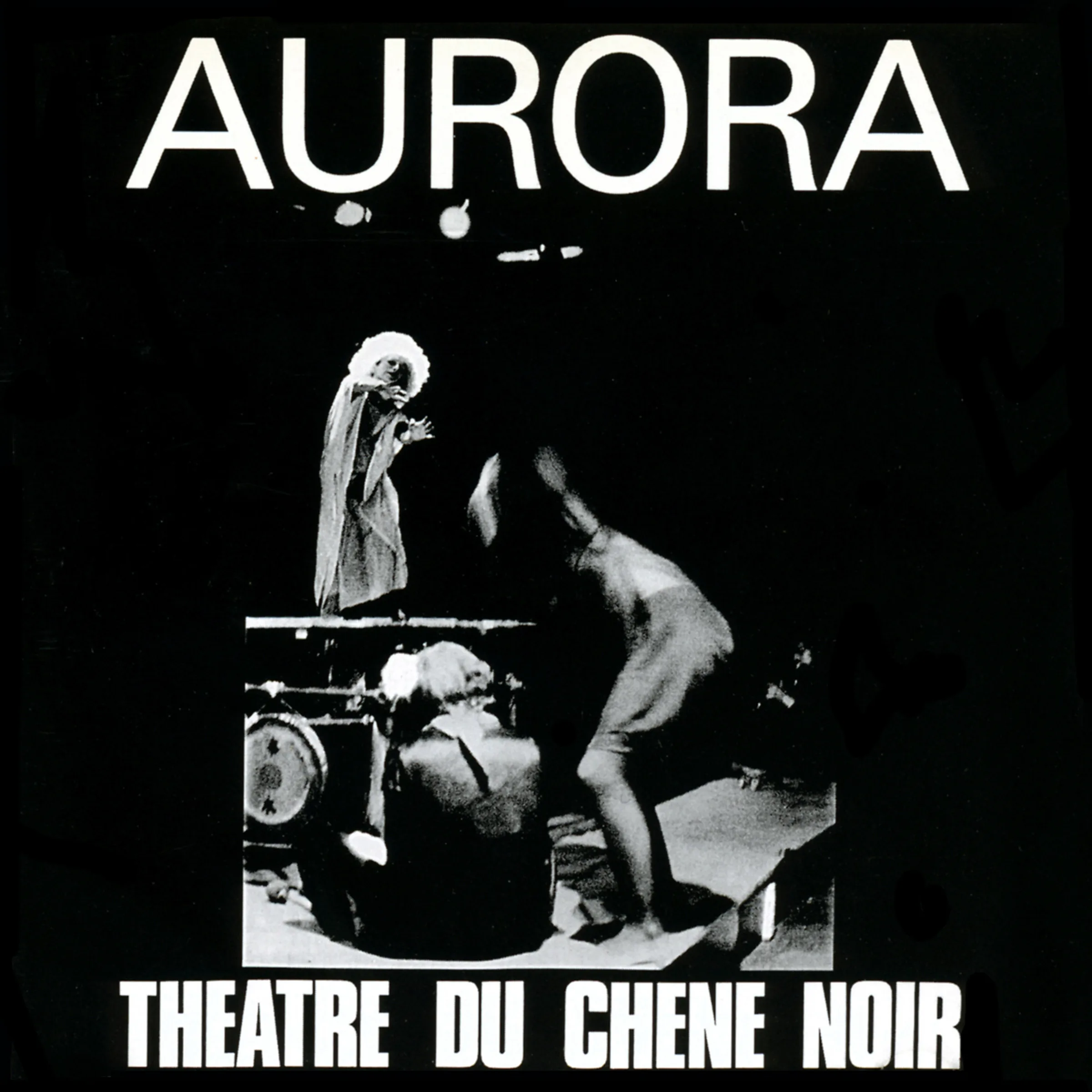

Théâtre du Chêne Noir

Aurora

In 1966, a French playwright by the name of Gerald Gélas brought together a dramatic ensemble under the name of Théâtre du Chêne Noir (‘Theater of The Black Oak’) with the debut performance of his “Poèmes” staged in a small Avignon bistro. Although accompanied only by a trio, the troupe soon flourished so that in two years time Chêne Noir were comprised of a group of artists twice the size that, like Gélas himself, performed onstage with words, movement and music. With a variety of primarily acoustic instruments they performed literal melodramas (‘melodrama’ itself a word derived from the French ‘mélodrame’ meaning ‘musical drama’) that were economical and effectively integrated with Gélas’ direction.

Offstage events surrounding the 1968 ‘Festival Off’ programme of the Avignon Theatre Festival would unpredictably pitch Gélas and his ensemble into the public eye. On the afternoon of July 18, prior to Chêne Noir’s scheduled presentation of Gélas’ “La Paillasse Aux Seins Nus” (‘A Bare Breasted Prostitute Past Her Prime’) the Prefect of the Gard prohibits the performance, publicly determining “it may be detrimental to public order and cause harm to the Head of State.” A secondary cause for the ban was the performance location chosen by Gélas in between two collapsed towers in the ruins of the former monastery of the Chartreuse de Villeneuve. Notwithstanding the potential safety hazards of the proposed setting, it was more the presumably anti-Gaullist sentiments of “La Paillasse” that presented repercussions for which the city did not wish to be held accountable.

But in the wake of this ruling, other repercussions quickly followed. Fellow theatre directors taking part in the festival were outraged at the ruling and solidarity with Gélas was proclaimed. Choreographer Maurice Béjart went so far as to invite Chêne Noir to the courtyard stage of the Cour d’Honneur within the huge Palais des Papes for his performance of “A Mass For The Present Time.” Symbolising the ban, Gélas and his company lay on the stage floor gagged while Béjart’s dancers danced on and over their bodies for the entire ninety minute performance.

Only two months after the student riots in Paris, the Avignon authorities had warily approached the forthcoming outdoor festival. However, the ban on Gélas’ theatrical presentation caused the air of contentious unrest to rise until French riot police were called in to dispel the agitated protesters. An altogether different kind of drama ensued, as not only protesters but theatre-goers and tourists were caught in the outbreaks of violence and arrests.

In the wake of this unfortunate publicity, Chêne Noir received an invitation to perform in Rome. Here, Gélas met Federico Fellini and many other overachieving Italian artists of the dramatic arts. Newly reinvigorated and seeking to put the events of the past summer behind him, he returned to Avignon with the dream to ‘mount a popular theatre for all’ and during the course of the next three years he set about writing, directing and staging five performances with Chêne Noir: “Radio Mon Amour,” “Vivre Debout,” “Sarcophage,” “Marylin” and “Opéra-tion.” In September of 1970 came his ninth stage presentation, “L’Aurore” (“Aurora”) of which two successive performances from June 22 and 23, 1971 recorded and subsequently released on album by the experimental Futura Records label. (By the time the album was released, Gélas had secured a permanent space for Chêne Noir in a deconsecrated twelfth century chapel in Avignon, where it remains active to the present day.)

Within the grooves of “Aurora” came a strange and otherworldly environment with the sounds of a great dramatic spectacle slowly unfolding as the actor/musicians acted/performed their various roles onstage. Influenced by the French poet Antonin Artaud, it was the ‘dark forces’ of his Theatre of Cruelty that informed much of “Aurora” with its onstage musical instruments, undecorated stage without sets, vocal intonations instead of poetic language and accent on spectacle. The music bears the weight of the performance as their costumes were simple, the lighting severe and the props nonexistent. Chêne Noir practiced “Aurora” until its process was entirely absorbed and all the sounds from their hearts, heads and hands became one massive ritual reenactment of a combined set of creation and fall from grace mythologies. On record, the ambiance is that of a live recording done under chiaroscuro-lit conditions with its suspenseful and sparsely-assembled musical accompaniment coming across more as soundtrack of extended ruminations on a set of related themes than songs. Bringing forth a combination of drama, music and narrative, it drove the play throughout a series of lulling instrumental passages to severe percussion freak-outs, fits of screaming all encased within timeless motifs and an overall dark, Mediterranean vibe. Comprised of atmospheric musical strands with narration, screaming and little in the way of singing, “Aurora” captures the seven-piece Chêne Noir’s onstage vocalising and music-making with the lineup of: Nicole Aubiat (vocals, cymbals), Pierre Surtel (flute, alto sax, voice) Jean-Marie Redon (flute, voice), Guy Paquin (violoncello, trumpet), Daniel Dublet (gongs, bongos, bowed electric guitar, voice) and Gérard Gélas (drums, gongs and direction.)

The album begins with the extended drift piece, “Arrivée De La Terre Et De Ses Enfants: L’AURORE” (“Arrival Of The Earth And Her Children: AURORA.”) Like a Nino Rota theme to a black and white film of unknown vintage, an evocative and lonely flute slowly blows a mournful theme simple and rustic. Tempered by the gradual rising of wordless vocalisations from main chanteuse and demoiselle d’Avignon Nicole Aubiat, accompanying male voices join in chanting while shimmering cymbals and gongs resound all around as bowed violoncello hangs low in the background. Everything simmers down to leave the flute as sole accompany Aubiat’s incantation as Mother Earth, listing her natural gifts of the earth, the sun, the air and love to her newborn children so that they may live in happiness. With “Le Bonheur” (“Happiness”) the pace builds into something more frantic than a spirited romp of joy so that it feels as if shrouded with an invisible weight. The flute quickly picks up, playing agitated and fast-paced lines that weave and dance crazily inside hollow tom-tom patterning absorbed from “Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun.” With a sudden decrease in tempo, both flute and bowed electric guitar fall into softness and slip away.

The improvisational freak-out “La Vieillesse Et La Mort” (“Old Age And Death”) begins with the incantations of second female vocalist Bénédicte Maulet, her vocal directives cutting through surrounding simmering gong tones and sustained, high-pitched violoncello. A choir of voices keeps to a wordless drone until punctuated by a relapse into a stream of agonised and accusatory vocalisations that throw themselves into spastic, strained cries and startling screams. In turn, a spontaneous improvisation of discord breaks out with clattering drums, cymbals and flurries of blurting sax while the pair of droning devices, violoncello and bowed electric guitar, continue to screech and saw at the air like the acoustic rendition of “European Son”/“L.A. Blues” as played by French dramatists that it is. Soon, the psychic smoke clears to reveal Maulet as a dying crone unleashing further moans and growls as she claws at the ground.

Side two recommences with a piece about as long as its title. “Le Conte De La Terre Et De Ses Enfants Et La Première Apparition Des Hommes-Oiseaux” (“The Tale Of The Earth And Her Children And The First Appearance Of The Man-Birds”) starts quietly with whistling winds transmitting airborne contaminants as cymbals and gongs lightly ring. Flute reappears and starts to weave crazily into an assembled chanting choir and just as a spirit force seems to rise up and out from the shrillness of the fluttering flute and the woeful wordless chorus, everything halts into a near-standstill of quietude where the lowered and ever-mournful flute merges with the voices only to fall away into a sombre setting for Aubiat’s narration. As distraught Mother Earth, she slowly recounts how her children have been deceived into mortality by the corruption of mysterious agents from outer space the Men-Birds. Her tone is controlled and it’s shocking when it pitches suddenly into a higher register with a subsequent pileup of blaring saxophone along with an extended fit of gong and cymbal bashing shrill enough to drown out even her howling accusations. When it finally ceases, Aubiat gives her final heartbroken recitation of how the greatest gift of all she has bestowed upon her children — love — has been stolen by the Men-Birds, causing them to age and die. After her final undying affirmation of “la vie…” the remaining voices to be heard are those only of the Men-Birds. Bellowing harshly to rumbling tom-tom accompaniment, their complete domination of earth’s land, oceans, air and now her children are complete. All of this is documented in “La Fascination Des Enfants De La Terre Par Les Hommes-Oiseaux” (“The Fascination of The Children of The Earth By The Man-Birds”) with soft, mournful cries drifting among simmering cymbal tones, gently-bowed electric guitar and irregular bongo hits. Mournful wailings grow in strength until the Men Birds’ final hypnotic incantation seals the fate of humanity as an enslaved race. All voices fade into complete silence. Suddenly, the last free man on earth is heard gasping with terror-stricken, shallow breaths. Turning to find himself surrounded by a flock of interstellar avian men who edge him off a precipice to his death, he lets out a piercing and agonised scream. As if to signal earth’s total captivity, tom-toms return to resound triumphantly and accelerate slowly into a mechanised steam engine rhythm rolling into the future upon tracks laid with crossties of humanity.

“Vivre” (“To Live”) ends the album’s performance with Pierre Surtel blowing a long and slow requiem on alto saxophone. Expressive of a long lost freedom, its measured notes neatly drop off into silence just long enough to confound expectation of its ending…and continue in this manner until it slowly fades before the house lights turn up into the silence of this world.

“Aurora” succeeds musically, dramatically and with its freak-out zone twists and turns of sudden pandemonium evokes an atmosphere so strong as to be nearly tangible. Through the work of Théâtre du Chêne Noir, Gérard Gélas wished to offer to the public stories ‘of spirituality, dreams, tragedy and comedy’ that men and women carry within themselves while “Aurora” remains the earliest recorded evidence of that vision fulfilled.