Kaleidoscope

A Beacon From Mars

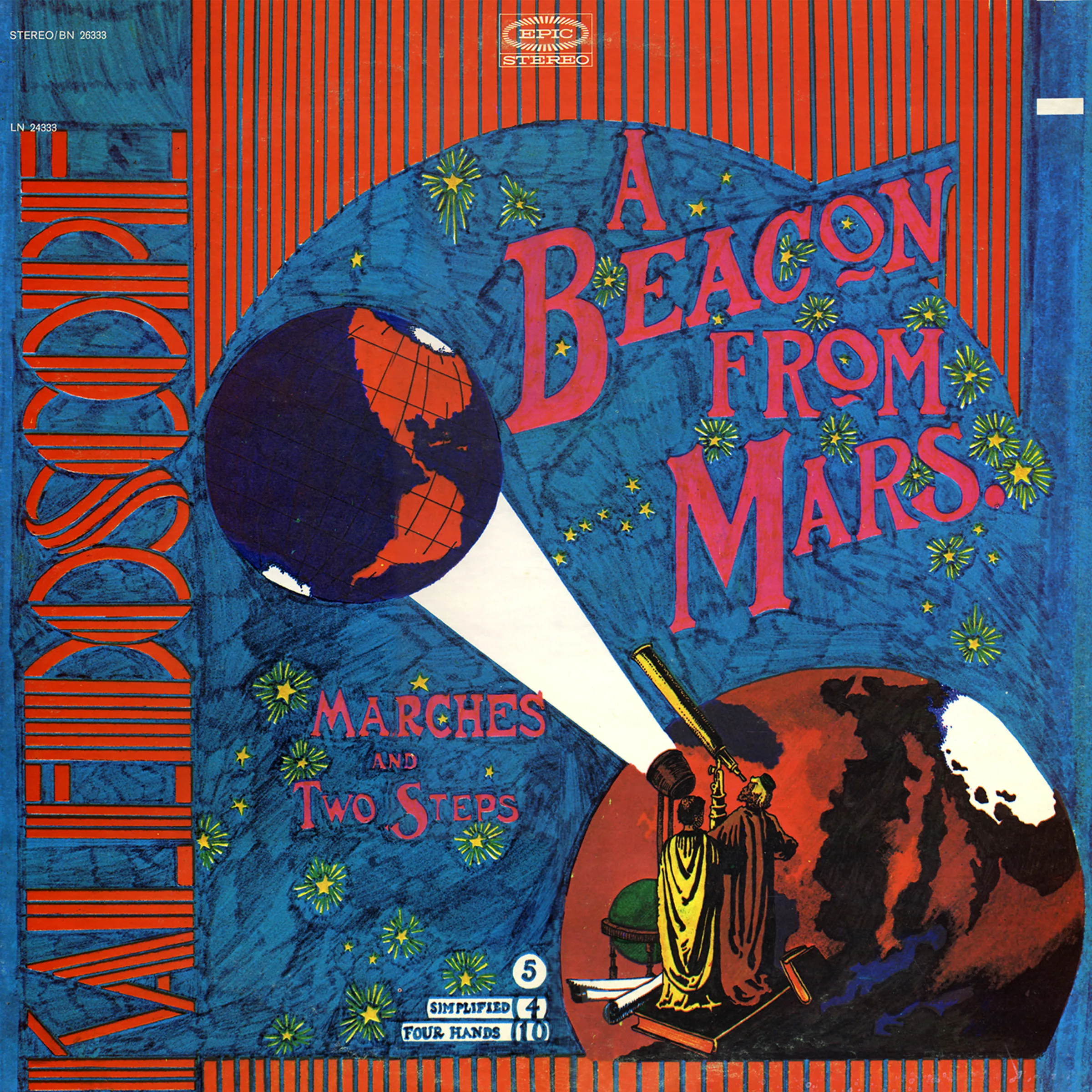

Although Los Angeles-based, one spin of this record is to totally understand why Kaleidoscope were so heartily embraced in the San Francisco ballroom scene of the late sixties. The tracks are all extremely diverse, their sounds an emanation more befitting a gipsy caravan campfire than of that of American ethno-blues acidhead band locked in a windowless New York City recording studio. And what they produced was an album of songs whose only linked characteristics is the complete embrace of each stylistically different genre every song mines so deeply. Whether old-time blues, folk, psychedelia or Turkish instrumentation, they are all about as strongly dosed as the black coffee Kaleidoscope’s vocalist and multi-instrumentalist Solomon Feldthouse preferred at this time. “A Beacon From Mars” was their second album, and already they were getting hassled by their management, label and producers. The album’s intended title was “A Bacon From Mars” taken from a line they had written about ‘pigmeat from outer space’! Wanting none of their freakiness, Epic vetoed its use and it was one of the few demands met by the group. But for reasons unknown, they did provide them with an amazing, George-Hunter/Global Propaganda-ish cover depicting two ancient astronomers casting a beacon on a red and black earth from a few miles off the coast of Mars. It looks like turn-of-the-last-century sheet music, but the only fitting dance to this album would be a Mr. Natural-inspired shuffle down the boulevard, not some stiff-backed Victorian foxtrot.

Kaleidoscope at this point featured David Lindley (guitar), Solomon Feldthouse (vocals), Maxwell Buda (keyboards), Chris Darrow (bass) and John Vidican (drums). But they all switch gear throughout with an array of wonderful and un-rock stringed instruments at the ready. The ellpee opens with “I Found Out,” a “Fifth Dimension”-ish post-acid illumination, all country plunk of folk and fiddles over Feldthouse’s craggy, Ottomaniac vocals. The folk dial gets turned to Appalachia all the way up for the traditional “Greenwood Sidee,” a murder ballad that unfurls a tale of life, death and ghosts, the lyrics returning to the title’s haunted locale over snares that roll in perpetuity. Lindley plays not only his huge harpguitar but joins Maxwell Buda on fiddle as well. “Life Will Pass You By” is a mass of fiddling and madly picked and strummed mandolins over the cautionary yet almost joyous vocals that warn “all that glitters is not gold.” “Taxim” follows, and is one of two recorded live-in-the-studio-with-no-overdubs centrepieces per side. An twelve-minute plus instrumental that emerges slowly at first, and winds up building into an exotic Middle-Eastern patterning trance led by Feldthouse’s caz and oud playing. It’s about as big as all the countries Feldthouse drew musical influences from, and about as sensuous as a full moon harem. Side two is every bit as varied. “Bald-Headed End Of A Broom” is in the vein of Hot Tuna’s later “Keep on Truckin’,” with its goofball lyrics and good-timey acoustic guitar, trad arr as hell. The instrumental coda gets all zany and sped up at the end, followed by a cover of “Louisiana Man,” where a clutch of fiddles and down home singing illustrate uncomplicated Delta life, rendered slowly and steadily. After it ends the ethnic instruments are laid aside for the rest of side two. The blues-based “You Don’t Love Me” opens with Lindley’s fuzztone-fried guitar but the following epic, “A Beacon From Mars” takes “Smokestack Lightnin’” on a twelve minute plus, live-in-the-studio odyssey with no overdubs. You really get lost in this one if you’re not paying attention. Tiny feedback squeaks and a Manzarek-like organ line signals for the rest of the band to falls in. Which they do, and no sooner does it pick up speed with high-pitched harmonica tweets, but it falls away far too soon. The “Stranger In Your City” segment is then hijacked by a long Lindley feedback solo and at times, his soaring feedback soliloquy is the only thing that revives the band back from ebb tide. The end features broken volume knob manipulations as the organ is switched between piano, harpsichord and back again. The band continually falls away, but always return when the vibe is right for them, as they’re playing musical chairs in an effort to freak you out. And they do: because when it all fades for the final time, you’re waiting for it to pick up again…only it doesn’t.