Brian Eno

The Shutov Assembly

With a succession of experimental audio, visual, and simultaneous audio-visual creations Brian Eno has been bringing to the culture table for the past several art decades, it’s probably ambient music that has been his most influential contribution. Taking the better part of fifteen years for the term to enter the mainstream, in the span of time between the release of his first ambient album, “Discreet Music” (1975) and the advent of new age along with post-house/techno’s fallout into MDA comedown/chillout some years later, it’s strange to consider how a music form proposed by its creator to be “as ignorable as it is interesting” went ignored for as long as it did — only to be embraced so fully at a much later date.

A highly unassuming set of ten audio situations (it’s still strange for me to consider them ‘songs,’ per se) “The Shutov Assembly” is a beautiful album and a meticulous singularity that sets itself apart from Eno’s previous six solo ambient works: “Discreet Music” (1975), “Music For Films” (1978), “Ambient 1: Music For Airports” (1979), “Ambient 4: On Land” (1982), “Apollo: Atmospheres And Soundtracks” (1983) and “Thursday Afternoon” (1985). “The Shutov Assembly” arrived after a seven-year absence of solo releases (ambient or otherwise) in the wake of “Nerve Net” and a companion remix CD of “Fractal Zoom” and it held an integration of elements more subtle and uncategorisable than previous and contained overall shorter pieces whose depths belied their length with a far greater variety of sonic shapes and textures. Where once Eno had applied occasional field recordings, now those throngs were replicated deftly with modified electronic processing or worked into the pieces with far finer application. The understated qualities of the tracks within create a wide and reflective space where signal transmissions approximate the speed of deep breathing while the sensitivity applied to those signal outputs (with or without various signal modification processes) create situations of thriving spaces of interplay and interconnectedness. Remaining effortless at all times, it’s as though these pieces could nudge on infinitively with their self-generating properties — organic as drifting tides, falling shadows and other gradual, natural occurrences. These results derived from obscured, treated instrumentation, unknown source materials (and in all certainty: a fair amount of theoretical experimentation) are at the heart of this album’s mystery.

“The Shutov Assembly” was also unique in that it was Eno’s first solo ambient album to stand alone without liner notes, graphic representations of the pieces, working methods or any explanation as to its theoretical framework. However, a record company promotional press kit for the album did include a brief overview by Eno of the album’s origins and aims: “I want to make the music as one would make a painting — to create a believable space teeming with life — with concordances and tensions, with a network of focal points and no clear hierarchy between them.” Also, for the first time on a solo Eno album the music was the sole creation of Eno with no outside collaborators and he is credited with ‘all instruments.’ Outside of sparse piano, synthesizer and synthesized treatments via synthesizer, recording console or tape, these instruments remain mostly unidentifiable throughout. (The album also existed outside of any predetermined theme with its only unifying thread that all pieces were recorded during 1985–1992 and originally culled by Eno for Sergei Shutov, a Russian painter for whom the album takes its name.)

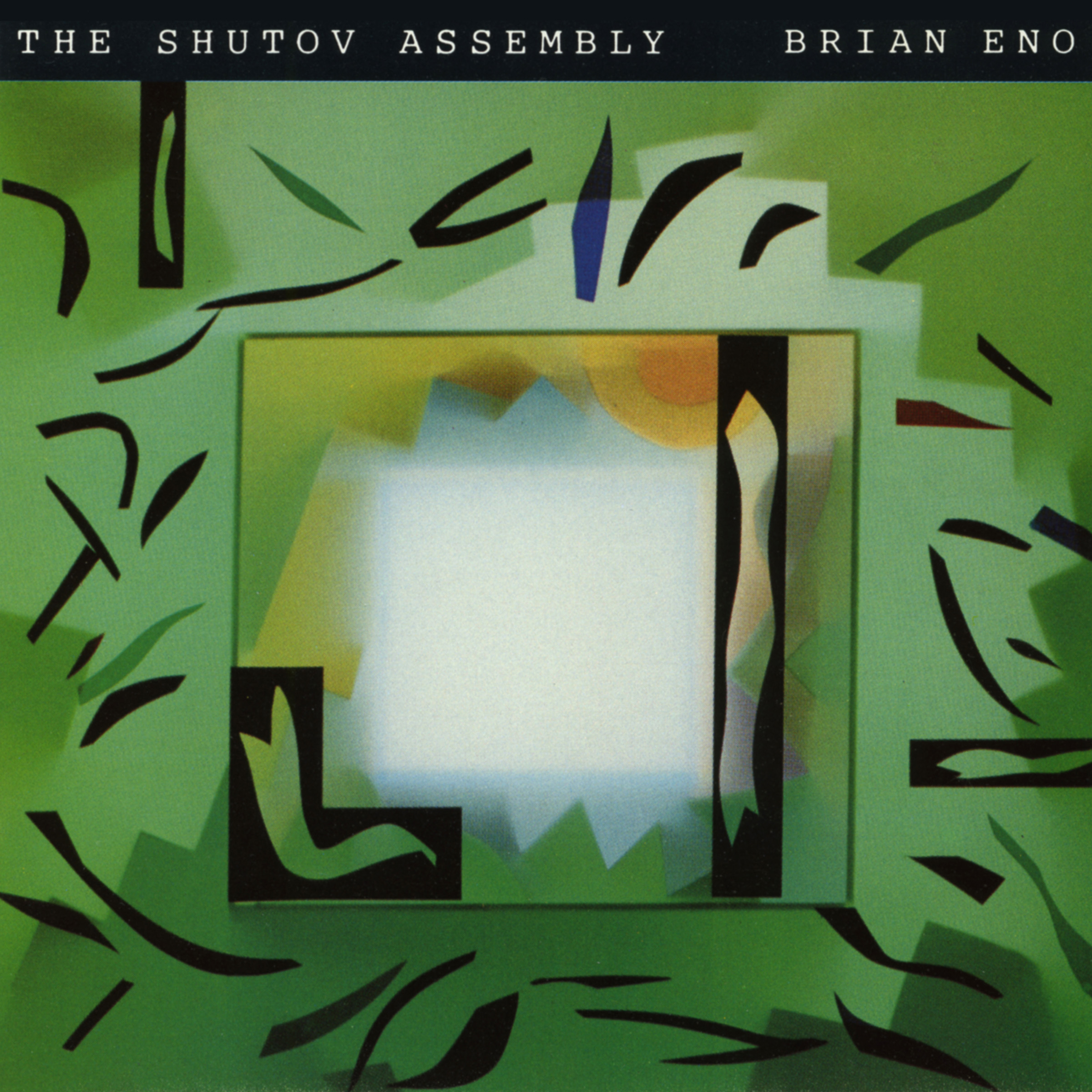

Framing is a concept that Eno applied to his other ambient releases in one respect or another, but it was especially prevalent on “The Shutov Assembly.” The front cover is a still from a video painting by Eno that reflects this sense of location: the frame as art and the art as frame with the music framing the space you experience it in. (For instance, I’m now listening to this album at low volume under the blue August moon with an actual symphony of nighttime insects outside two opposing windows. A Venn diagram of this arrangement of outside to inside sounds is hovering into a single circle.) A glimpse of the back cover reveals 10 track titles all 9 letters in length, set up in a 9 by 10 block of text. This is framed by four different hued versions of the front cover stacked vertically on the left, while a UPC code is wildly stretched to its total 5 inch height to the right. (At least on the Opal/WB version as the reissue on All Saints dispensed with the UPC code.) Here, one could also make a point about the possible symbolism of art and commerce, but onto the music before I set off on a series of art school flashbacks (as if I haven’t already…)

Engaging on several levels, the tracks seem more glimpses of audio procedures where there is (technically) not much going on but also a lot going on (technically.) “Triennale” begins the album with a series of twittering birds and twinkling eddies of glittery notes in impressionist daubs of colour that arrive in soft focus and remain there. Twice (or maybe three times) waves quietly crash in the distance. Gracefully treading (and ever so slowly) between melody and melodic insinuation, the notes continue to arrive relaxed in a measured, near-random flow…“Alhondiga” crosses the threshold into darker yet just as spacious terrain. Dark shadings with ominous rumblings, twinkling of bell-like signals and quietly menacing keyboard plant an unrequited melody line that diffuses and inexplicably sounds not altogether different from the opening sequence of Pink Floyd’s “A Saucerful of Secrets” (of all things)…“Markgraph” begins gently with a mutedly-shaped keyboard bass that nudges by in patient clusters at the speed of knitting. A floating shimmer of high notes held to pinpoint drop of wavering feedback at the pitch of moistened finger circumnavigating the rim of a wine glass reappear over ghostly vapours suggesting distant voicings. Iridescent tones continue to waft in and over shadowy, Farfisa organ-like clusters until all dissipates…“Lanzarote” is the most spacious and airy moment of the album. Originally released as “Glint (East of Woodbridge)” on a clear flexi-disc in the January, 1986 issue of Artforum magazine, without the benefit of the inherent surface noise of that long distant format, here “Lanzarote” becomes even more successful a representation in sound of stillness. Cricket non-menace. Sounds extend into the wind…Two piano notes, wavering and muted whispers of distant voice-like tones that intimate sounds just out of range. Slowly, a soft arpeggiated bass resounds. By the time of its gradual fade, you wonder how it became so entirely dissimilar from its commencing patterns and then “Francisco” materialises with shuddering pitch applications set on a reoccurring series of notes held into suspended freefall. Distant bass masses resound in the distance. Whirring: a signal split three-way with one extremely high-pitched. Signal decreases but keeps right on the edge of evenly-sustained, quiet but shrill feedback…“Riverside” is a passage that lulls in water-like currents while simultaneously conjuring up a dark, flat field with one small light in the distant perched on the distant edge of the horizon. Flute-like tones skate across weightlessly while iridescent shimmer pervades. Gradations shaded into diffusion…“Innocenti” is a sweet and icy segment of purposeful aimlessness. Twinkling, crystal clear, high-pitched and water drips sensually. Tones modulate with silky, liquid sounds…“Stedelijk” cuts in with a repeating pair of notes in the process of falling away into echo, low tones. Then a passage reminiscent of an entirely unconstructed and highly nuanced version of (once again) the opening segment of “A Saucerful Of Secrets” emerges. Echoed skittering, protrusions of moaning bass undercurrents and a series of Farfisa-like notes reoccur in its unplotted orbit of deep space…

The longest piece of the album, “Ikebukuro” stands out from the rest of the album not only in terms of its length but its highly repetitive series of hollow bell tones accompanied by a mysterious swooping rotor blade sound that cuts in and out and at varying intervals as though on a heavily elongated and irregular loop. Alongside this are sparse, electric piano-like tones that cluster into Mediterranean church bell intonations while the arrhythmic whipping (sometimes suggesting a flailing mammal, sometimes a downed helicopter and often: neither) cross in shadows over the settled, arid dust of late afternoon shadows in a De Chirico landscape like the deserted plazas in Antonioni’s “L’avventura” as dry heat and long shadows draw down a late afternoon of equally late summer. What first entered as an interruption soon becomes an accepted part of the environment because its sheer repetitive representation has long insinuated itself into the pattern. The presence of unknown and obscure audio events pervade in the background of the omnipresent chiming tones of the long now and the big here. HERE…Which is returned to with the fade out once a small piece of equipment accidentally lands with a flat thud…“Cavallino” finishes the album with iciness and intrigue. Expansive choral tones hold to everlasting sustain as tiny, frozen signals fade in and out in circular motion from beneath an unspecified surface.

Any sense of narrative is dispensed with on “The Shutov Assembly” while its continuous flow encourages a space beyond the perimeters of the album. Its mysterious play of colours and textures remain indefinable, alluring, and exquisite all at once.